Creating a Land Registry for a Network State

3 approaches for creating a crypto-native land ownership system

Last month’s newsletter, How Close Are We to Digital-Native Property Records?, left this question unanswered:

What if you had land that was outside the jurisdiction of an existing country? Where the land ownership records were reset and you were starting from scratch? .... This could be a Network State purchasing an island where the Network State owns the island free and clear - it is not beholden to the laws of previous owner or its system of property rights. What would that actually look like?

In this newsletter, I’ll look at three approaches to answering the question. I’ll start with the most centralized and ordered approach, contrast it with the most chaotic, and then end with an approach that is somewhere in the middle (and my favorite).

The Master Plan

Upon establishing the Network State, the government would hire an urban designer to create a master plan for the entire geographic area. The plan would be complete with roads, parks, urban nodes, and parcel boundaries. This obviously only works at a small scale - you couldn’t hire an urban designer to design the road and parcel network for the entirety of United States, at least you wouldn’t be able to do it all at once. Once the design is complete, the Network State government would register each of the parcels in a land registry (via blockchain), and then establish the rules and process for who gets to claim a parcel (and how many, and at what cost).

In this approach, the shapes of parcels designed via master plan would likely respond to natural features like ridges and rivers; parcel shapes could be curvilinear and would not be uniform. The shapes would be determined by an overall design plan which might consider views, topography, watersheds, transportation networks, projected land use, and food systems. Parcel size would vary; smaller parcels where property is expected to be more valuable, or in areas imagined for higher density residential areas.

Comparisons

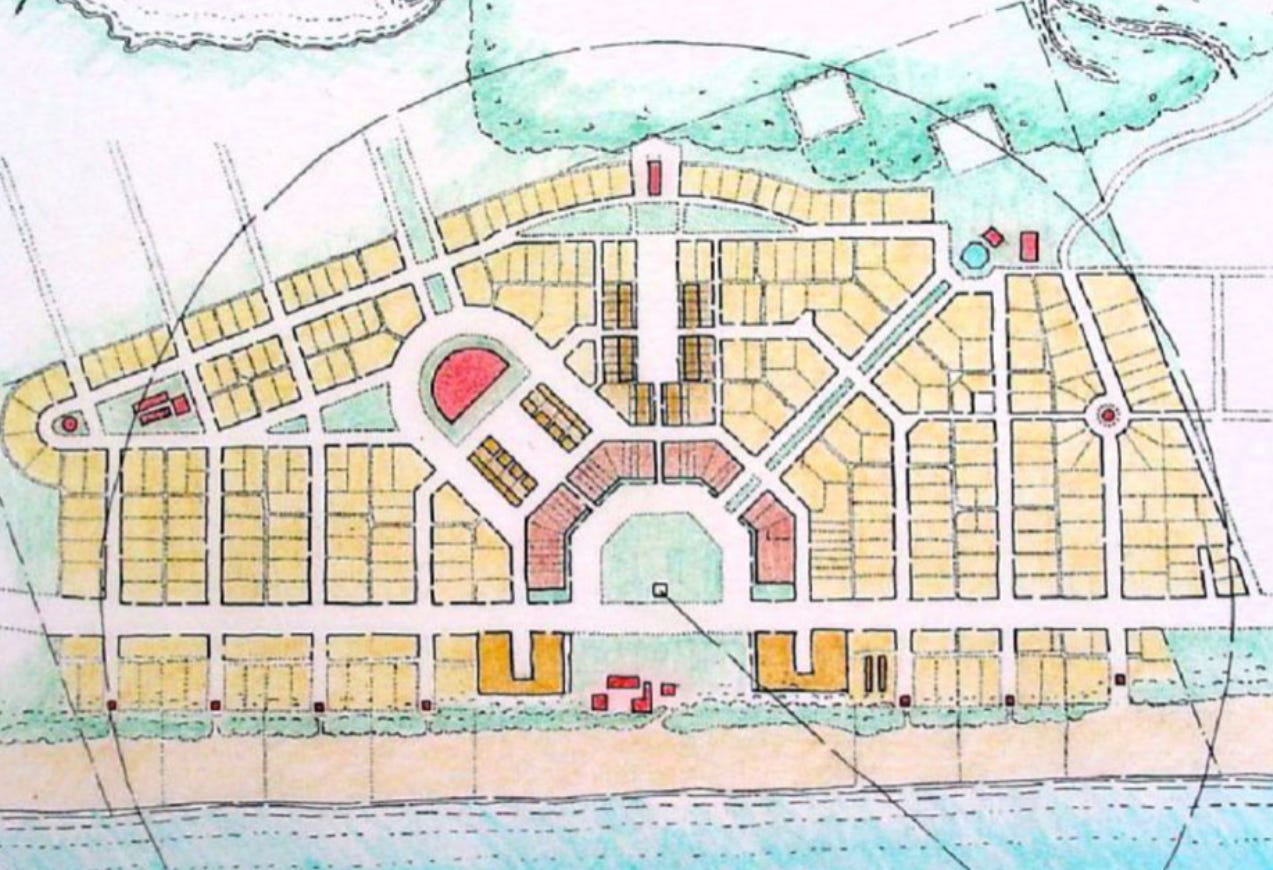

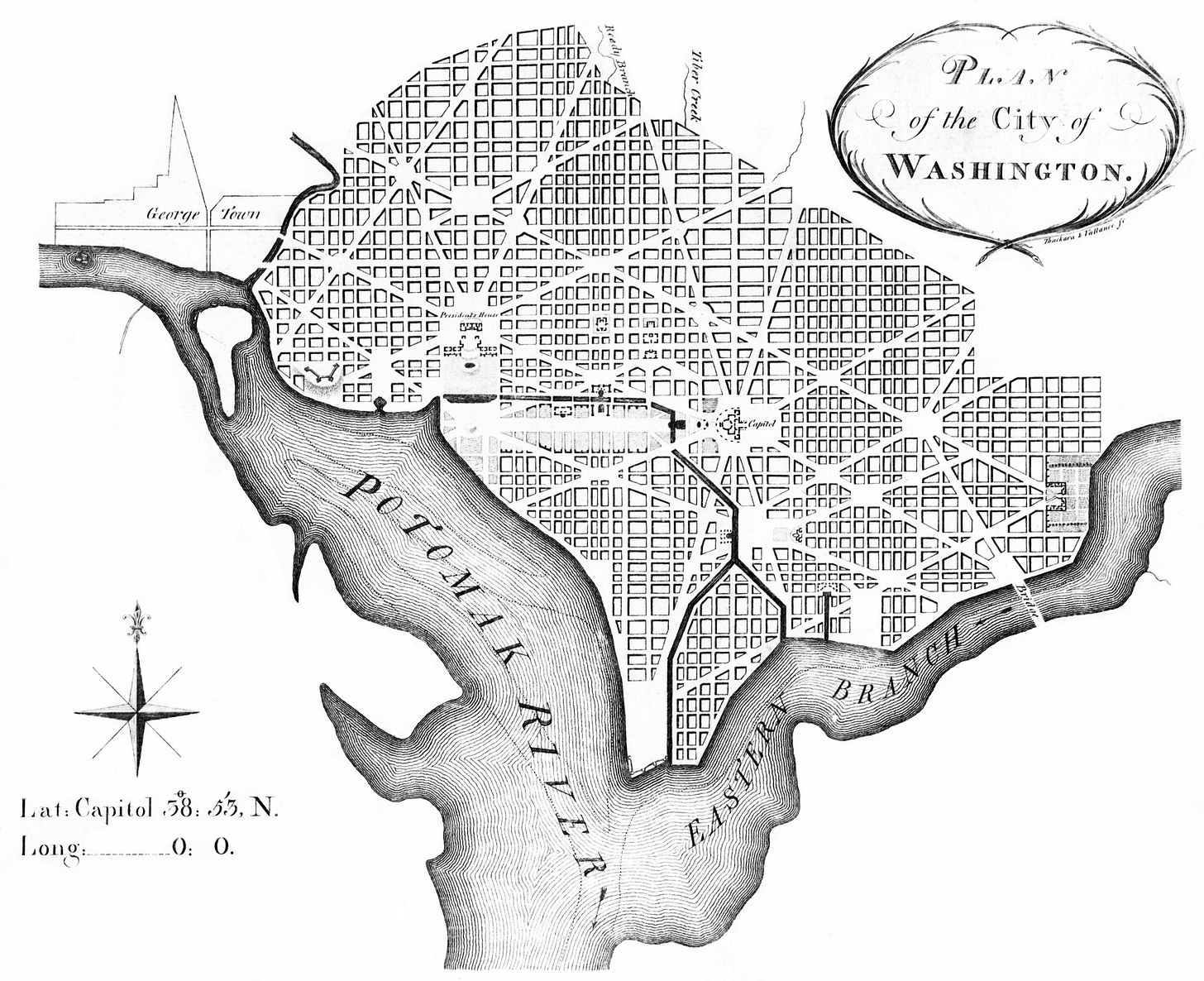

Planned Cities: There are many, many, examples of designed cities and towns throughout urban planning history (click on the footnotes to see images of the plans). They include small towns like Radburn, New Jersey, and Seaside, Florida.1 Radburn’s key feature was creating separate transportation networks for pedestrians and automobiles. Seaside was designed in the new-urbanist style which focused on creating dense, but charming spaces for pedestrians. There are also city-scale examples (listed in chronological order with plan images in footnotes): Washington DC,2 Canberra, Brasilia, and Chandigarh.3 These planned capital cities are all designed to project order and grandeur. And in these examples, the plans only determine the block structure; parcels within the block are either left for private development to determine later or planned in separate drawings.4

In all cases, the underlying goals of the city’s design (transportation efficiency, dense walkable neighborhoods, or desire appear organized and grand) ultimately informed the shape and size of the parcels within. While the purpose of this comparison is just to describe one way parcel shapes can be generated, it’s worth noting that the success of these master planned cities varies greatly. The longevity of success (if any) is usually limited by how evergreen or universal whatever its primary concept was. For example; a town planned around automobiles was great in the 1960s and 1970s, but now a desire for walkable urban living has returned, and cities that planned for efficient movement of cars but not pedestrians are no longer as desirable.

Satoshi Island is a more recent, crypto-related example. The entire island (1.15 square miles / 3 square kilometers) has been planned out by landscape architect James Law, with predetermined parcel sizes, roads, and open space. There are a total of 2,100 parcels within seven neighborhoods like “East Cliff” where parcels are designed to take advantage of expansive views, or “Satoshi Central” where parcels are near the island’s central park and entertainment zones. The island is the territory of the country of Vanatu, and is owned by Satoshi Island LLC. So its not truly a Network State, but since it’s all owned by one property owner, subdividing the property and selling the subdivided parcels as land NFTs is functionally equivalent to starting with a blank slate.

The Free Form Free-for-All

Upon establishing the Network State, all of the land in the newly minted state would be up for grabs. It would be land without title. The Network State would establish the rules and process for who gets to claim a property (and when, how big, and at what cost). The Network State government would maintain the land registry (via blockchain) once claims begin.

In this approach, the shapes of newly claimed parcels would be free form. It wouldn’t have to be straight lines and right angles. Parcel boundaries could be curvilinear, nonuniform. They could follow a river, valley, ridge, or some other natural feature. Or, the parcel shape could be a geographic version of Boaty McBoatface that pleased its original possessor. Some initially claimed properties could be huge, while others may only be big enough to support a tiny home. It could be totally market-based, or lightly regulated by the Network State with some rules about a parcel's size or shape.5 Or, instead of a "first come, first-served" approach to parcel choice, there could be an algorithm to decide on parcel shape. For example, the state could give all citizens a month to place a pin on a map where they want their property to be, and then an algorithm determines property boundaries based on something like a Voronoi Growth Euclidean6 (its a cool GIF, see it in the footnote!).

Comparisons

Land Grants in Colonial America are excellent examples of a free form approach. When the British arrived in the Americas in 1607, they basically stated all unclaimed land was now property of the King.7 The King then rewarded his supporters with property in America through land grants, like the Fairfax Grant in Virginia.8 Early land grants were large - the Fairfax Grant was over 8,000 square miles (21,000 square km) - and could be any shape. Typically they used rivers and streams as parcel boundaries, so shapes were certainly free form. Land grants were not really a free-for-all though, as they were only given to a small number of the elite who had the right friends and connections.

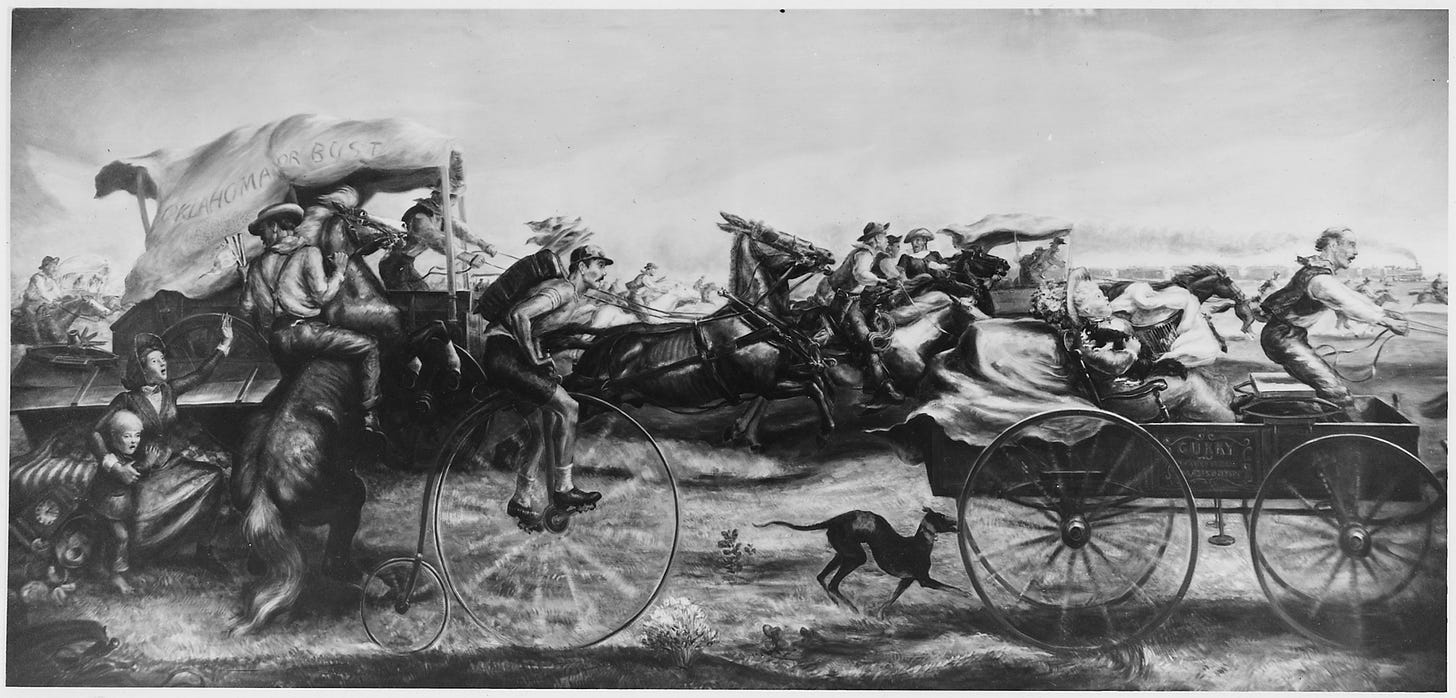

The Homestead Act and The Land Rush of 1889 are good examples of a free-for-all approach; the latter is depicted in the image for this section. In 1862 the United States passed into law the Homestead Act which ultimately granted 270 million acres (190 million hectares) of land, in 160 acre (65 hectare) parcels free to U.S. residents who met certain conditions. #Airdrop! The giving away of land (that wasn’t really for the United States to give… it originally belonged to Native Americans) happened over many years in a series of land rushes. One of the most notable was the Land Rush of 1889, where at the sound of a gun, the government opened 2 million acres of land in Oklahoma, in 160 acre plots, available on a first come, first serve basis. This was quite literally a free-for-all. Whoever physically got to a plot first was declared the owner. In this case though, the parcel shapes were predetermined, so not exactly free-form.

The Micro Grid

Upon establishing the Network State, the government would divide the entire territory into uniform cells of the same size. The cells would define the basic unit of land, where each cell in the grid is an indivisible unit. A cell could not be further subdivided. The Network State would establish the rules and process for who gets to claim a cell (and how many, and at what cost). A citizen could own multiple contiguous cells and develop it as a single property. They could sell off one or more cells from their property, but there would be no process for selling a portion of a cell. The Network State government would maintain the land registry (via blockchain) once claims begin.

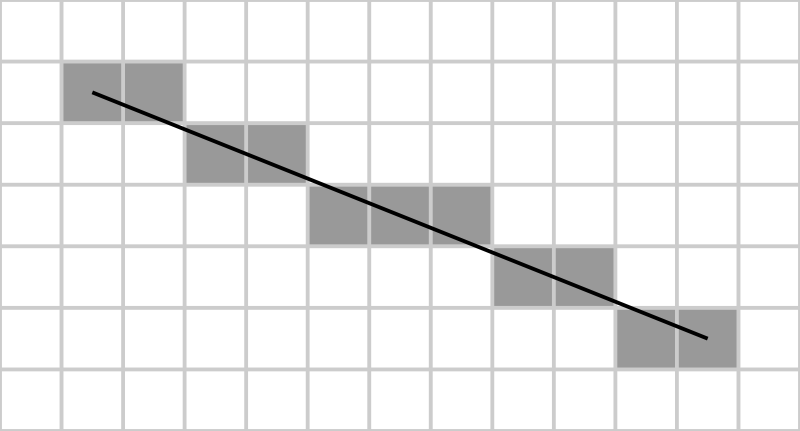

In this approach, the shape of each cell would be a square (like TV pixels) or hexagon (Settlers of Catan!) with necessary adjustments to account for the convergence of lines of longitude towards the poles. Cells would not adjust to topography or any other real world consideration. But they would be small. How small?

At one mile square (like the Jefferson Grid visible in the section image header),9 the cell size is too large and the result is that they have to be subdivided. The goal here is to choose a cell size as small as possible - but not too small as to be overkill or unwieldy in terms of data storage or practical usage. For real property in cities, I would guess the range would be between 1 square centimeter and 1 square meter (explorations of this particular topic in a future newsletter!).

Why does having an indivisible unit matter? It makes record keeping and ownership transfers so much more efficient. If you want to sell a portion of your land to your neighbor, there is no complicated legal process; no requirement to get a new survey and a new parcel boundary drawn. You just transfer the NFT of the cells of interest and you are done. It’s unclear whether the legibility of such a system and ease of transfer is worth the potential data storage headaches, or cases where the cells at the boundary of your property are inefficiently used.10 But I’m still intrigued.

Comparisons

The Jefferson Grid and the Public Land Survey System (PLSS) established 1 square mile (2.6 sq km) cells for previously unsurveyed land in the United States. The grid system made it very easy to survey large tracts of new land during America’s westward expansion, as opposed to the previous metes and bounds survey system. The system also had an interesting effect on urban design that you can see in aerial photos of the American west and in the header image. Most notably, roads are straight and rectilinear, following the cell boundaries. The obvious difference between the PLSS and the microgrid is the size of the parcel. At 1 square mile, parcels might be ok as a basic unit for farms or ranches, but would require subdivision if you wanted to have any kind of density in a city.

Geoweb is a digital land registry for the entire earth, where you can “own” any ~5 meter by ~5 meter square of the earth if you win that cell’s online auction, and pay an annual fee. Owning a cell in geoweb doesn’t mean you actually have property rights IRL for that corresponding cell, but its easy enough to imagine a Network State where owning the digital cell also means you own the IRL cell. I’d imagine the microgrid approach would work very similarly, the notable difference here is the size of the cells in geoweb, which are too big to be useful as an indivisible unit of real property.

r/Place was the social experiment that let Reddit users (almost 1 million participated) change one pixel at a time (every 5 to 20 minutes) on a 1,000 pixel by 1,000 pixel digital canvas. If we imagine that the digital canvas was instead a map of real property, the comparison is a little more clear. While individuals could control one pixel at a time, if an individual collaborated with multiple redditors (which many did), they could control multiple contiguous pixels to create a legible image; sort of like the ability to combine multiple cells together in the microgrid approach to create a usable property.

The (short) Case for the Micro Grid

If you assume that the land registry will stick around for 50+ years, its inevitable that property boundaries will be redrawn in both the master plan and free form approaches. Master plans represent the designer’s best guess for that moment in time on how a city might develop, and even the most well planned cities will need to adjust as technologies change and cities grow. Free form parcel designs are great for the original property owner, but are unlikely to be exactly what the next owner wanted or needed. If a blockchain based land registry is required to have the ability to redraw property boundaries and re-issue real property NFTs it would certainly add complexity.

You wouldn’t need that ability with a micro grid approach, though the initial set up might be more complex. The benefit of the micro grid is that you are simply providing the framework for future land use plans and parcel designs. You can still have free form designs (assuming the cell size is small enough), and can more easily redesign your city if necessary. For example, imagine how much easier it would be with a microgrid to either expand or reduce the width of a street right of way to account for new transportation technologies. I’m not saying the micro grid doesn’t have problems (data storage, cell size and curvature of the earth, mapping accuracy for 1 cm cells) but if they can be resolved, the micro grid seems like the most elegant, flexible, and efficient approach to a crypto-native land registry.

Tags: hashGovernance hashLandUseAndProperty

Footnotes

Some cities in the United States have regulations to limit the creation of “irregular lots” or lots smaller than a certain size.

I just kind of gloss over this to keep the newsletter more concise, but this is truly mind boggling audacity. Showing up to a new place and being like “Yup, this is mine now… never mind you people that have been living here before!”

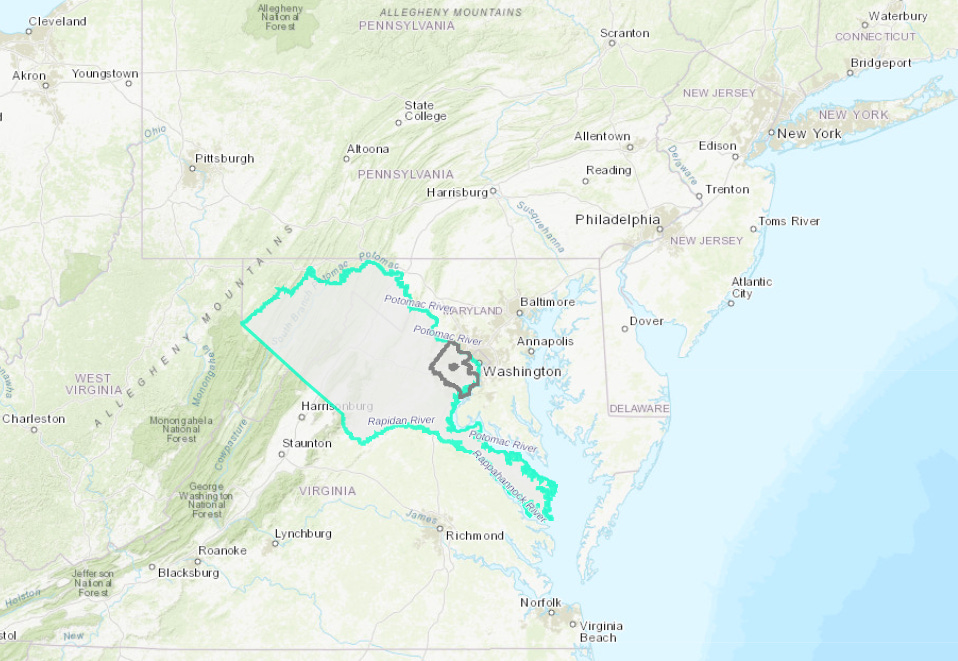

Read more about the history of the Fairfax Grant here. The grant in question is shown in the light green boundary - a huge area west of present day Washington, DC.

The Jefferson Grid is readily apparent throughout much of the United States, including in this photo of Hereford, Texas.